Using Breakpoints

This module assumes you know how to launch termmines in

Ghidra using GDB and know where to find the basic Debugger GUI

components. If not, please refer to the previous modules.

This module will address the Breakpoints window in more depth. While the breakpoint manager is able to deal with a system of targets, we will only deal with a single target at a time.

Breakpoints

Most likely, this window is empty if you have been following the lesson.

From here, you can toggle and delete existing breakpoints. There are several ways to set a new breakpoint:

- From any static or dynamic listing window, including Disassembly,

Memory/Hex, and the Decompiler, right-click and select

Set

Breakpoint, press K on the keyboard, or double-click

the margin.

Set

Breakpoint, press K on the keyboard, or double-click

the margin. - From the Objects window click the

Add

Breakpoint button or press F3 on the keyboard.

Add

Breakpoint button or press F3 on the keyboard. - From the Interpreter window, use the GDB command, e.g.,

break main.

The advantage of using the listings is that you can quickly set a

breakpoint at any address. The advantage of using the Objects or

Interpreter window is that you can specify something other than an

address. Often, those specifications still resolve to addresses, and

Ghidra will display them. Ghidra will memorize breakpoints by recording

them as special bookmarks in the imported program. There is some

iconography to communicate the various states of a breakpoint. When all

is well and normal, you should only see enabled  and

disabled

and

disabled  breakpoints. If the target is terminated

(or not launched yet), you may also see ineffective

breakpoints. If the target is terminated

(or not launched yet), you may also see ineffective  breakpoints.

breakpoints.

Examining Minesweeper Board Setup

Suppose we want to cheat at termmines. We might like to

understand how the mines are placed. Knowing that the mines are placed

randomly, we might hypothesize that it is using the srand

and rand functions from the C standard library. While we

can test that hypothesis by examining the imports statically, we might

also like to record some actual values, so we will approach this

dynamically. (This is the Debugger course, after all.) The breakpoint on

srand will allow us to capture the random seed. The

breakpoint on rand will help us find the algorithm that

places the mines.

Set the Breakpoints

In the Interpreter, type the GDB commands to set breakpoints on

srand and rand:

break srand

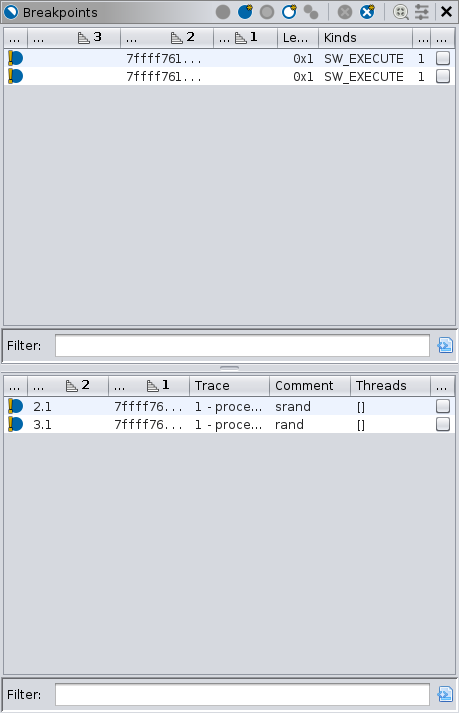

break randThe breakpoint window should now be updated:

For a single target, the lower panel of the Breakpoints window does not add much information, but it does have some. We will start with the top panel. This lists the “logical” breakpoints, preferring static addresses.

- The left-most column Enabled indicates the

breakpoint’s state. Here, we see the inconsistent

overlay, because Ghidra cannot save the breakpoint without a module

image. That is because

overlay, because Ghidra cannot save the breakpoint without a module

image. That is because srandandrandare in a different module, and we have not yet imported it into Ghidra. - The next column Name is the name of the breakpoint. This is for informational purposes only. You can rename a breakpoint however you like, and it will have no effect on the target nor back-end debugger.

- The next column Address gives the address of the breakpoint. Notice that the addresses were resolved, even though the breakpoints were specified by symbol. Typically, this is the static address of the breakpoint; however, if the module image is not imported, yet, this will be the dynamic address, subject to relocation or ASLR.

- The next column Image gives the name of the imported image containing the breakpoint. Again, because the module has not been imported yet, this column is blank.

- The next column Length gives the length of the breakpoint. In GDB, this generally applies to watchpoints only.

- The next column Kinds gives the kinds of

breakpoint. Most breakpoints are software execution breakpoints,

indicated by “SW_EXECUTE.” That is, they are implemented by patching the

target’s memory with a special instruction (

INT3on x86) that traps execution. There are also hardware execution breakpoints indicated by “HW_EXECUTE,” and access breakpoints indicated by “HW_READ” and/or “HW_WRITE”. NOTE: GDB would call these “watchpoints.” An advantage to software breakpoints is that you can have a practically unlimited number of them. Some disadvantages are they can be detected easily, and they are limited to execution breakpoints. - The next column Locations counts the number of locations for the breakpoint. For a single-target session, this should always be 1.

- The final column Sleigh is only applicable to the emulator. It indicates that the breakpoint’s behavior has been customized with Sleigh code. This is covered in Emulation.

Now, we move to the bottom panel. This lists the breakpoint locations, as reported by the back-end debugger(s). The Enabled, Address, and Sleigh columns are the same as the top, but for the individual dynamic addresses.

- The Name column is the name as designated by the back-end.

- The Trace column indicates which target contains the location. The text here should match one of the tabs from the Threads panel.

- The Comment column is a user-defined comment. Its

default value is the specification that generated it, e.g.,

srand. - The Threads column indicates if the breakpoint is scoped to a limited set of threads. Its use is atypical.

Toggling the Breakpoints

While there is no need to toggle the breakpoints right now, it is a good time to demonstrate the feature. There are several ways to toggle a breakpoint:

- In any listing, as in setting a breakpoint, right-click and select a toggle action, press K on the keyboard, or double-click its icon in the margin.

- From the Objects window, expand the Breakpoints node, right-click a breakpoint and select Toggle or press T on the keyboard.

- From the Breakpoints window, single-click the breakpoint’s status icon, right-click an entry and select a toggle action, or create a selection and use a toggling action from the local toolbar. Either panel works, but the top panel is preferred to keep the breakpoints consistent. The local toolbar also has actions for toggling all breakpoints in the session.

- From the Interpreter window, use the GDB commands, e.g.,

disable 2.

Practice toggling them. Notice that no matter how you toggle the

breakpoints, the display updates. You might also type

info break into the Interpreter to confirm the effect of

toggling breakpoints in the GUI. When you are finished, ensure both

breakpoints are enabled.

Importing libc

While the Debugger can operate without importing external modules, it

generally works better when you have. The symbols srand and

rand are in libc. If you would like to save

the breakpoints we placed on them, you must import the module. You could

do this in the usual manner, but the Debugger offers a convenient way to

import missing modules.

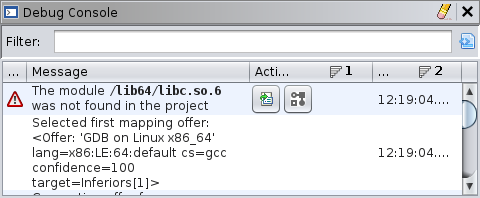

Navigate to a dynamic address that would be mapped to the missing module. For our scenario, the easiest way to do that is to double-click an address in the Breakpoints window. Either one points somewhere in

libc.Check the Debug Console window for a note about the missing module:

Click the import button — leftmost of the remedial actions. It will display a file browser pointed at the library file.

Proceed with the import and initial analysis as you would in the CodeBrowser.

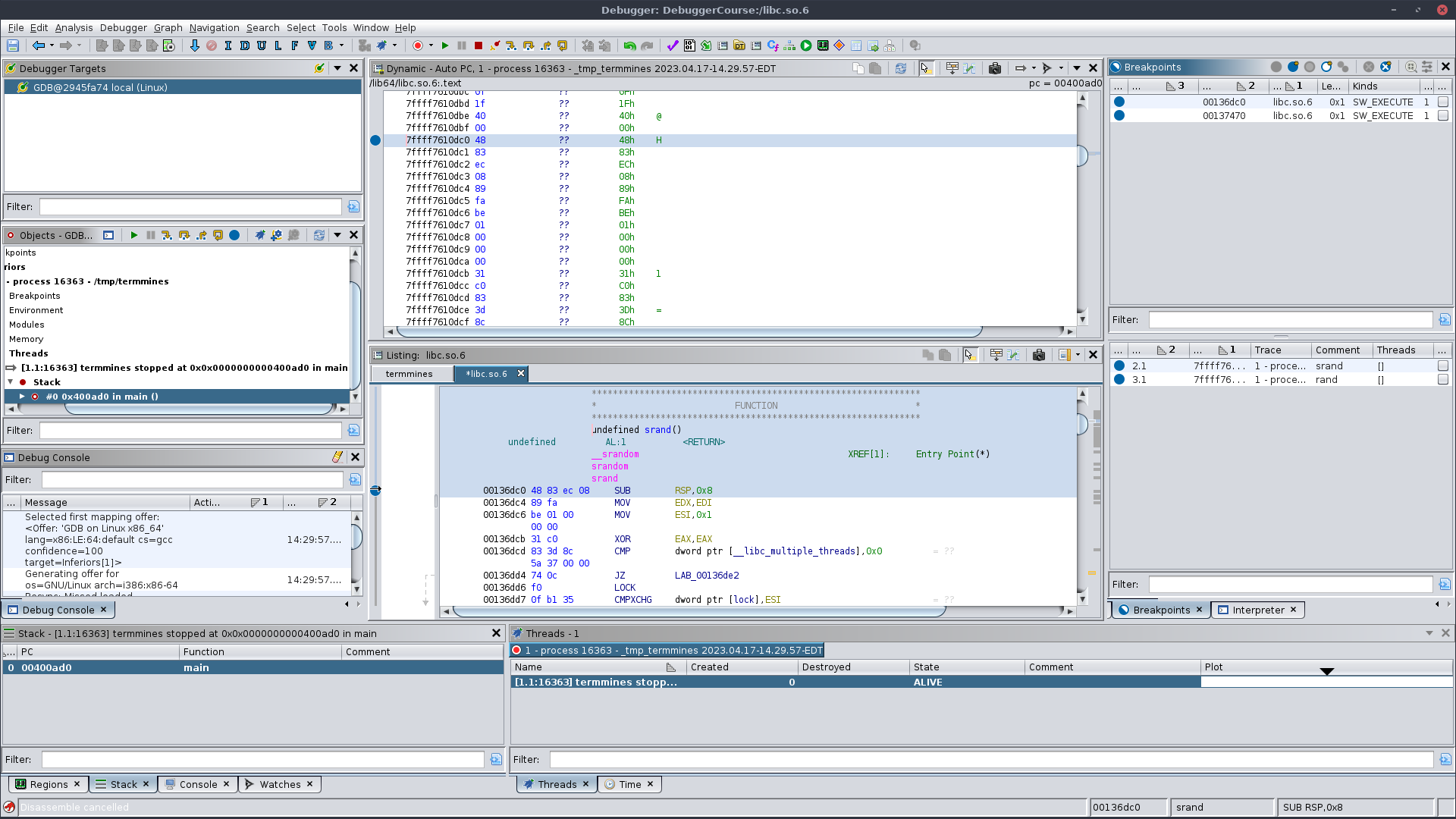

Once imported, the Breakpoints window should update to reflect the

static addresses, the breakpoints should become consistent, and the

Static Listing should now be synchronized when navigating within

libc.

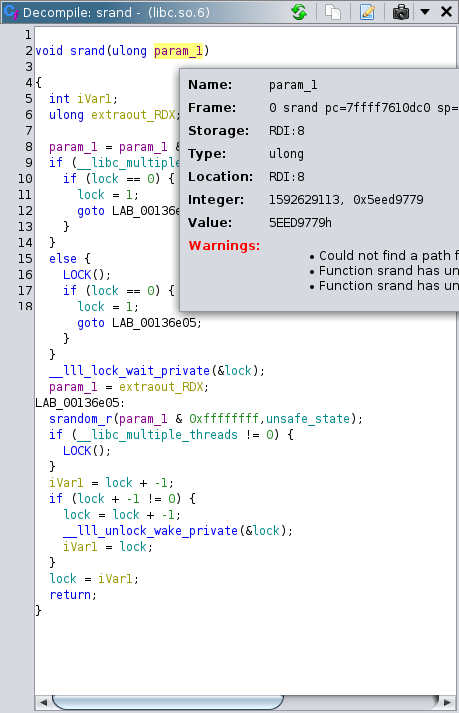

Capturing the Random Seed

We can now allow termmines to execute, expecting it to

hit the srand breakpoint first. Click  Resume. If all goes well, the

target should break at

Resume. If all goes well, the

target should break at srand. If you have never written

code that uses srand before, you should briefly read its

manual page. It takes a single parameter, the desired seed. That

parameter contains the seed this very moment! We can then examine the

value of the seed by hovering over param_1 in the

decompiler.

We will cover other ways to examine memory and registers in the Machine State module. We have contrived

termmines so that its random seed will always start with

0x5eed____. If you see that in the value displayed, then

you have successfully recovered the seed. This seed will be used in an

optional exercise at the end of this module. You might write it down;

however, if you re-launch termmines between now and then,

you will have a different seed.

Locating the Mine Placement Algorithm

Press  Resume again. This

time, the target should break at

Resume again. This

time, the target should break at rand. We are not

interested in the rand function itself, but rather how the

placement algorithm is using it. Press  Step Out to allow the target to return from

Step Out to allow the target to return from

rand. If you still have the Decompiler up, you should be in

a code block resembling:

while (iVar2 = DAT_00604164, iVar1 = DAT_00604160, iVar10 < _DAT_00604168) {

iVar3 = rand();

iVar2 = DAT_00604164;

iVar11 = rand();

lVar7 = (long)(iVar11 % iVar2 + 1) * 0x20 + (long)(iVar3 % iVar1 + 1);

bVar14 = *(byte *)((long)&DAT_00604160 + lVar7 + 0x1c);

if (-1 < (char)bVar14) {

iVar10 = iVar10 + 1;

*(byte *)((long)&DAT_00604160 + lVar7 + 0x1c) = bVar14 | 0x80;

}

}If you are thinking, “I could have just found rand in

the symbol table and followed its XRefs,” you are correct. However, it

is useful to use a dynamic debugging session to drive your analysis

chronologically through execution of the target, even if much of that

analysis is still static. The advantages of a dynamic session along side

static analysis should become more apparent as you progress through this

course.

Exercise: Diagram the Mines

You goal is to capture the location of all the mines. So that you can

check your work later, you should run termmines in a

terminal and attach to it from Ghidra. You will probably want to disable

the breakpoints on rand and srand for now.

Devise a strategy using breakpoints and the control buttons (Step,

Resume, etc.) so that you can observe the location of each mine. Use pen

and paper to draw a diagram of the board, and mark the location of each

mine as you observe the algorithm placing it. There should only be 10

mines in Beginner mode. Once the mines are placed, press  Resume. Check you work by

winning the game. Alternatively, you can intentionally lose to have the

game reveal the mines.

Resume. Check you work by

winning the game. Alternatively, you can intentionally lose to have the

game reveal the mines.

Optional Exercise: Replicate the Boards (Forward Engineering)

You will need a C development environment for this exercise. Because,

as we have now confirmed, termmines is importing its random

number generator from the system, we can write a program that uses that

same generator. Further, because we can capture the seed, and we know

the placement algorithm, we can perfectly replicate the sequence of game

boards for any termmines session.

Write a program that takes a seed from the user and prints a diagram

of the first game board with the mines indicated. Optionally, have it

print each subsequent game board when the user presses ENTER. Check your

work by re-launching termmines (see note about attaching

below), capturing its seed, inputting it into your program, and then

winning the game. Optionally, win 2 more games in the same session.

NOTE: We will need a more advanced attaching

technique to check your work, because you will need both to break on

srand (which happens early in the process’ execution,

ruling out our usual attach technique) and to interact with it in the

terminal (which rules out launching in Ghidra). There are a few ways

around this, including using gdbserver or using

set inferior-tty. If you are already familiar with those,

you can try one. The technique we recommend here is using a stub that

will suspend itself and then execute termmines. We can then

run the stub in a terminal outside of Ghidra, attach to that stub, and

then allow it to proceed into termmines. In this way, we

can attach to the process in the terminal before it reaches

srand. The stub is fairly easy to write in Bash and should

be similar in other shells.

In a terminal running Bash (see note if you’re using

anyptracer):(echo $BASHPID; kill -SIGSTOP $BASHPID; exec ./termmines)The parentheses will start

bashin a new subprocess. The first two commands cause it to print its own process ID and then suspend itself. Your terminal should display the PID and report the stopped process.NOTE: If you need to use the

anyptracerstub, then the invocation is more complicated:./anyptracer 'exec bash -c "echo $BASHPID; kill -SIGSTOP $BASHPID; exec ./termmines"'In principle, it works the same except wrapped in the

anyptracerstub. The parentheses are no longer needed, nor allowed, sinceanyptraceris already a subprocess of your shell. If you include parentheses, you will get a second sub-subprocess to which you cannot attach.In Ghidra, follow the usual steps to attach, but use the PID printed in your terminal. NOTE: The process is still technically running

bashwhen you attach to it.In the Interpreter panel:

break mainNOTE: At this point

maintechnically refers to the symbol inbash, but GDB will adjust its location once the target loadstermmines.Back in your terminal running Bash:

fgThis will cause Bash to return the stub to the foreground of the terminal. Without this step, the system will repeatedly suspend the process whenever it attempts any I/O on that terminal.

In Ghidra, press Resume (or use

continuein the Interpreter) until you hit the breakpoint atmain. This permits the stub to complete its third commandexec ./termmines. Theexeccommand is different than normal command execution. Instead of creating a subprocess, it replaces the image of the stub process, so the process is now runningtermmines.Refresh the Modules node in the Objects window. You may need to clear your filter text. Expand the Modules node and verify it lists

termminesinstead ofbash. Without this step, your listings may go out of sync.

At this point, you are attached to your target running in the

terminal, and you have trapped it at main. Because you were

attached to it when it was still bash, you will likely see

a lot of extraneous history. For example, the Modules panel will report

many of the modules that had been loaded by bash. Please

note their lifespans, however. They should correctly indicate those

modules are no longer loaded. In any case, you now have the tools needed

to check your work for this exercise.